Workplace groups create their own

values over time through social and economic associations that can damage the

efficiency and financial viability of any organization. When organizations

develop their own group standards, that lay in productive and accurate

perceptions, their premises can encourage higher levels of organizational performance.

Inappropriately socialized members often develop their own groups which

influence the organizational culture and costs of transactions throughout their

networks. Left untouched the groups’

decisions become less logical and more damaging to the financial success of the

total organization. It is important for executives to understand how they

groups form and the potential wide reaching problems they can create.

It is first beneficial to define what

a group is. Groups perceive themselves as belonging to the same social unit (Lawler,

Thye, and Yoon 2008). Their place in society is defined by their shared

experiences and understandings. To change a group member’s identity and perceived

station in life requires the ability to change both self-perception and the

members of their social group. This is one of the reasons why a poor organizational

culture can be improved by moving employees to new locations and bringing in fresh

members with outside perceptions.

When members see themselves as part of a group they

begin to view each other as having similar characteristics and traits that bind

them together. The group is a method of moderating self-interest and seeking

positive perceptions of each other (Ellemers, Spears, and Doosje, 1997). Once

initiated into a group, the members begin to view each other as more worthwhile

and having more positive traits than those who exist outside the group. Within an organization, in and out-group

mentality can create encampment, hoarding of resources, and influence the

financial success of the entire organization through poor decision making.

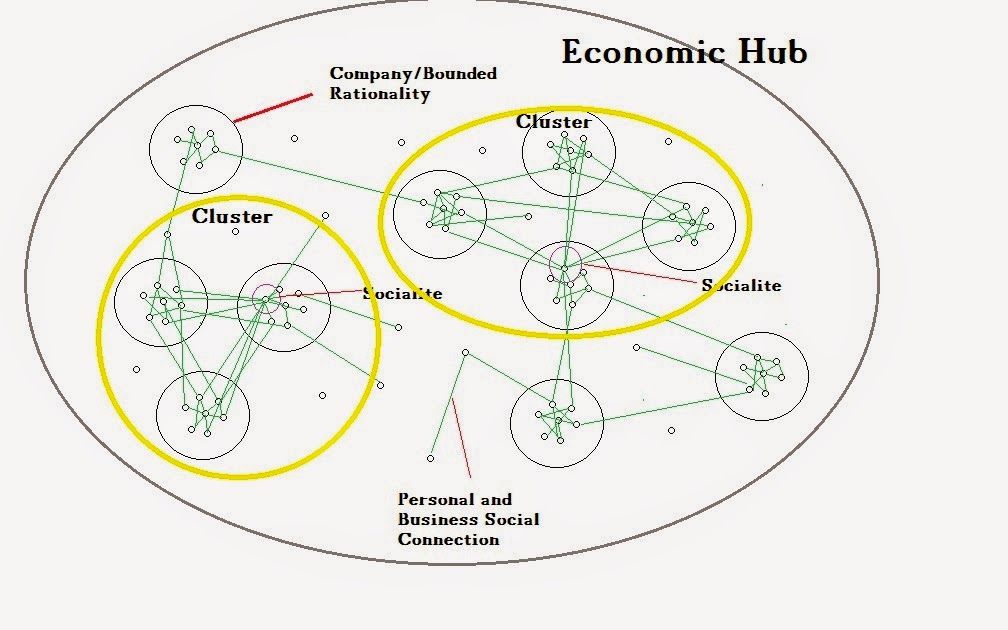

This can be expected as groups seek to create

advantages for their individual members at the exclusion of competing

organizational interests. They do this through the formation of a group network

that continues to expand throughout the organization. According to Thye, Lawler

and Yoon actors a) perceive the network as a group; and , b) share rewards and resources with each

other when opportunities arise (2011). Such

networks will continue to seek additional rewards and resources even at the

expense of their employer and society.

Within the group certain behaviors will produce

certain reactions and results from participating members. As long as these

behaviors continue to produce the expected results the group members will remain

entrusted to each other. The actions that become dependent on the response from

other members are called social exchanges (Blau 1964). Groups live and breed these

social exchanges and common rules of engagement. Outside intervention by

managers and investors can be resented creating difficulty and passive

resistance to requested changes.

Since such groups have social, as

well as economic purposes, they create higher forms of identity the more these

needs are gratified. Such relational commitment further solidifies the identity

of group members which separates them from other groups (Cook and Emerson, 1984).

Each group has their own relational commitment assumptions that help them

define their distinct identities and existence. Outsiders may have difficulty

understanding the unique set of underlining assumptions the group is using to

define their identity and social interaction.

Over time the group becomes so

distinct that their identity creates new realities of perceiving the world.

According to social constructionists the group eventually uses their assumptions

to create “objective” perceptions of the world (Berger and Luckmann 1966). The person is thus fully embedded in the group

and therefore sees their existence from the vantage point of the group assumptions

and uses these assumptions to judge others and make strategic decisions. Any

management team, new executive, or consulting firm is seen as an outsider

attempting to intrude upon the groups identity which damages self-identity.

This is one reason why outside intervention is often staunchly opposed.

Such similarity in subjective

truth can define “stickiness” in economic decisions that are weighted and

judged against societal norms. Independent objective thought becomes more

difficult the more people define themselves based upon their distorted group

identity. Such relational identities impact both the sociological and economic

transactions of the members (Emerson 1981). Having two different economic

approaches within an organization can damage that organizational viability

through waste and inefficiency that is rooted in inappropriate premises.

At times the group identity can

be so far removed from organizational and societal norms that they run counter

to these wider expectations. Socially embedded market transactions can defy

rational thought and logic (DiMaggio and Louch 1998). Such logic creates their

own market influence based upon information sharing and thought patterns of

members who interpret environment actions from a skewed lens. Changing the

group identity and thought patterns requires exposing them to new people,

methods of needs attainment, and ways of thinking.

Group identity can either

encourage productive behavior or be destructive by nature. In organizations

group identity that is stronger than organizational norms should concern both

executives and investors. Such networks continue to expand their influence and

waste of organizational resources by financially and socially feeding group

members at the expense of more logical choices. It is through the development

of strong cultural assumptions and organizational identity that more effective

uses of organizational resources can be achieved.

Berger, P. and Luckmann, T. (1966).

The Social Construction of Reality.

New

York: Doubleday.

Blau, P. (1964). Exchange and Power in Social Life. New

York: John Wiley.

DiMaggio, P. and Louch, H. (1998).

Socially Embedded Consumer Transactions:

For What Kinds of Purchases Do

People Most Often Use Networks? American Sociological

Review 63:619–37.

Ellemers, N., Spears, R. and Doosje,

B. (1997). Sticking Together or Falling Apart: In-group Identification as a

Psychological Determinant of Group Commitment versus Individual Mobility.

Journal

of Personality and Social Psychology 72:617–26.

Emerson, R. (1981). Social Exchange Theory. pp. 30–65 in

Social Psychology: Sociological Perspectives, edited by M. Rosenberg and R. H.

Turner. New

York: Basic Books, Inc.

Cook, K. and Emerson, R. (1978) Power,

Equity, and Commitment in Exchange Networks. American Sociological Review 43:721–39.

Lawler, E., Thye, S, & Yoon,

J. (2008). Social Exchange and Micro Social Order. American

Sociological

Review 73:519–42.

Thye, S., Lawler, E. & Yoon, J. (2011). The

emergence of embedded relations and group formation in networks of competition.

Social Psychology Quarterly, 74 (4).